Broken Telephone Pictionary is a hoot of a party game. The way I learned it, strict rules say that each of 5 to 8 people around a table draw a thumb-sized picture at the top of a sheet of paper of something they can see from where they are sitting, to start. Less strict, just something actual, something that can be held in a hand or walked up to. No need to get fanciful, you see. Second, pass the paper to the right and describe in no more room what the person to the left drew, then fold over the picture, pass the description along. Now, draw what is described, fold over the description, pass that along. Continue until someone runs out of paper, then watch as the tension of not peeking erupts in hilarity at seeing how far the imagery gets from the original, and at seeing the immense variety of interpretations and choices made in continuing the chain of communication.

If you need to bust a gut laughing among friends or strangers, it’s a great way.

That came to mind as a contrast to the gamification of building trees of ancestors on MyHeritage or Ancestry. Both services show hints toward records that are possibly relevant to those already part of a tree someone has started. A marriage record or birth certificate can name parents, for instance, and a census record may then reveal siblings. The interfaces are pretty good, allowing people to get a look at scans of the original paper records before proceeding, and then letting them choose relevant details to include, rather than just clobbering whatever is already in the tree.

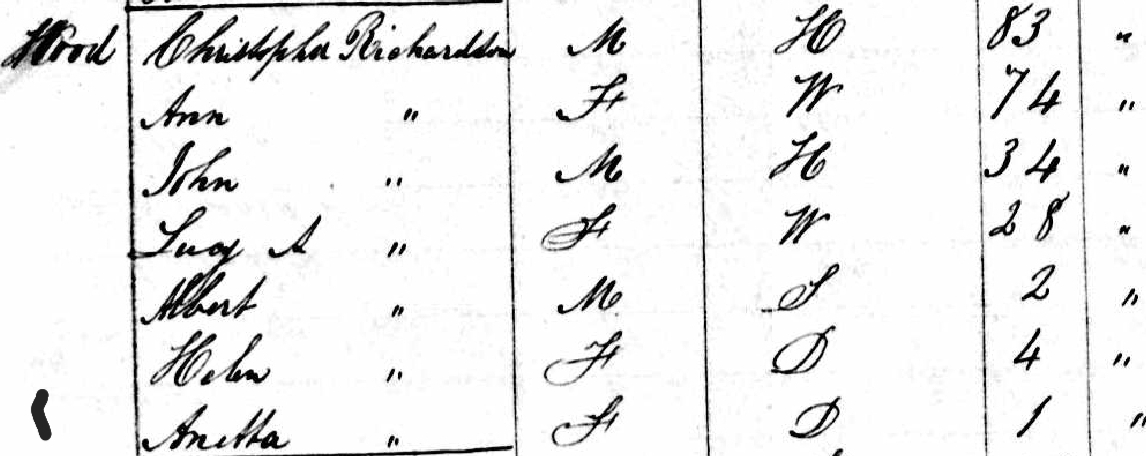

But there are mistakes. Misinterpretations of what data is what, sometimes. Many more mistranscriptions from records written in fountain pen ink. One of my great-grandmothers, for instance, was her middle name Julia or Cecilia? A book prepared by an archivist about the homesteading settlers where she was born says Julia and shows that one of her brothers married a Cecilia, a sister of the man she married, an easy source of confusion. But then I came across an image of a census record that showed Julia if you squint at it one way, and Lelia if you squint another. Considering that in the 19th century the ledger pages for the censuses were filled out by people stopping at one dwelling after another and hearing what they were writing down spoken aloud, either a mis-hearing or a moment of inattention while writing could result in Lelia being written down for Cecilia.

Or wrong dates: for the same great-grandmother, one census transcription shows a birth year of 1929, where all other sources show 1824. It’s easy to see how how that mistake was made, until looking down the column and seeing how 9 looks on other rows in that person’s handwriting. But of course the transcriber was reading across, not down.

Such slim pickings the official records are for connecting the pedigree dots. An 1851 census ledger page shows another of my great-grandparents at age 2 under the same roof as his parents and two of his grandparents, plus siblings … but aside from recording what the dwelling was made of, a one-letter code for relationship of each resident to the head of the household, a race listed as “B. American” — B. for British, presumably, when each entered the colony (never, they were all born in what was then called the colony of Nova Scotia), their occupation, and who was ill or infirm, there’s nothing there about the people themselves, or their lives.

The 1861 census was even starker that way: one line per household, one name recorded and then how many males and how many females in each of a number of age brackets. The legal fiction at the time was coveture: everyone in a household was under the protection of the patriarch, which made all the women and children, and any men who hadn’t been able to start their own household, effectively possessions of his by the mores of the day. There was an accounting of how many colonists there were; who they were was of no account to the authorities.

Building out trees of ancestors on the consumer DNA services is effectively a massively multiplayer cooperative game, but there’s no depth or sense of interaction to the experience, each player poking away at an app by themselves, connecting dots and little else. I’m going to continue and finish off attaching records as accurately as I can to the tree of people I am sure I am descended from, but it’s no party game.

So, how bizarrely bent out of shape are the pictures I have of them, made by looking at descriptions composed of database entries made from transcriptions of scans of microfilms of ledgers? That, and projections of what I think I know about how life was then? I’ll never know, but I have to figure all the removes hamper clear seeing. Could comparing pictures at least bring some good humour into the hopelessness of accurate communication over centuries by such spare means? I’d like to think so.

Leave a Reply